chicagotribune.com

Anti-corruption law: Supreme Court decision could derail ex-Gov. Rod Blagojevich's trial

Justices are asked to scale back or strike down prosecutors' key tool for public corruption cases

By David G. Savage,Tribune Newspapers, November 30, 2009

LINK

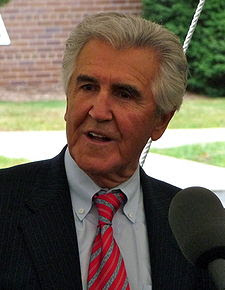

WASHINGTON -- The nation's most potent law against public corruption could be in danger of being scaled back or struck down by the Supreme Court, threatening a series of high-profile cases, including those of former Gov. Rod Blagojevich, (pictured above) the Washington lobbyists who worked for Jack Abramoff (pictured below testifying before the Senate Indian Affairs Committee)and several jailed corporate chiefs.

At issue in court arguments in early December is a ban on "honest-services fraud," (see full link copied below - Editor) often used against public officials who accept money, free tickets or well-paying jobs for their spouses and children in cases where bribery cannot be proved.

"In Chicago, this was our go-to statute. Every major public corruption case in the last 10 years relied heavily on an honest-services charge," said Patrick Collins, formerly a top anti-corruption prosecutor for U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald in Chicago. These cases include the conviction of former Gov. George Ryan.

The trial of Blagojevich is set to begin in June, but Collins said it could be derailed by a high court decision. "If the court were to gut the statute, the prosecution would have to think long and hard about how to restructure the case. (Honest-services fraud) is the core operating theory of the case," he said.

In Washington, anti-corruption activists fear the court's ruling could take away from prosecutors their best tool for combating the culture of gift giving and cozy deals between lobbyists and members of Congress and their staffs.

"It would undercut public corruption cases across the board," if the court struck down the law against honest-services fraud, said Melanie Sloan, executive director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

Opponents say honest-services fraud is vague and ill-defined. It fails to spell out, for example, the point when a friendship turns into a criminal scheme. Julian Solotorovsky, another former federal prosecutor in Chicago, said the court should strike down the law and force Congress to spell out what is a crime. "There is no vaguer statute on the books than this one," he said. "I'm surprised it's taken 21 years to get this before the Supreme Court."

In New York, the former state Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno is on trial in an honest-services fraud case for allegedly obtaining $3.2 million in private consulting fees from clients who had business before the legislature. His fate is before the jury.

Last month, a jury in Washington was told Abramoff's lobbying operation spent more than $5 million between 2000 and 2005 doling out free tickets to sporting events and concerts for members of Congress and their staffs. But the jury could not reach a verdict on a series of honest-services fraud charges against Kevin Ring, a former congressional staffer who worked for Abramoff. The judge put off a retrial until the Supreme Court rules on the law.

In recent decades the Supreme Court has made prosecuting public officials more difficult.

In 1987 the court threw out the use of mail fraud statutes against a Kentucky official who doled out the state's insurance business to his friends. However, there was no allegation that the deal resulted in a cost to the state's taxpayers. Congress responded by passing a one-line amendment saying a fraudulent scheme includes one to "deprive another of the intangible right of honest services."

In 1999 the justices limited the reach of another law against giving "illegal gratuities" to public officials because there was no proven link to "an official act."

Bribing a public official is also a crime, but it's hard to prove. Prosecutors must show an explicit deal between the official and the person offering the bribe.

In the two decades since Congress passed honest services, judges, prosecutors and defense lawyers have disagreed over its meaning.

In February, Justice Antonin Scalia sounded off in dissent when the court let stand the convictions of Robert Sorich and two other Chicago city officials for having schemed to steer city jobs to campaign workers. There was no allegation that Sorich and his co-conspirators had received any money.

Scalia said this open-ended law "invites abuse by headline-grabbing prosecutors" who can turn minor ethical lapses into a crime that carries a long prison term. Honest-services fraud is so broad it "would seemingly cover a salaried employee's phoning in sick to go to a ball game," he wrote.

Shortly afterward, the justices agreed to hear two appeals that call for paring back the law. In the first, Conrad Black, the jailed newspaper executive, argues that he cannot be held guilty of honest-services fraud unless it can be shown he intended to do economic harm to Hollinger International, the company he once headed. It formerly owned the Sun-Times.

And in Weyhrauch vs. U.S., a former Alaska legislator says he cannot be found guilty of fraud for failing to disclose that he had sought work with an oil services firm before he left the legislature. He did not get a job with the firm, but he did cast a vote in favor of the firm's position on a tax bill. Bruce Weyhrauch said the state's law did not require such disclosures, but federal prosecutors say he was still criminally dishonest. Both cases will be heard Dec. 8.

Last month, the court went further and agreed to hear a claim that the honest-services fraud law should be struck down entirely because it is unconstitutionally vague. The appeal came from former Enron CEO Jeff Skilling, who was convicted on multiple counts, including a fraud charge. Skilling says he was trying to save Enron from collapse, not defraud its shareholders. His case will be heard early next year.

The three cases have convinced lawyers that a major change is in the works.

dsavage@tribune.com

Honest Services Fraud

In 1988, Congress modified the mail and wire-fraud law by making it a crime to defraud citizens of their intangible rights to honest and impartial government. Since then, an increasing number of government officials have been indicted for depriving others of their honest services. This includes a pair of miscreant judges in Pennsylvania. The doctrine is a tool that may enable citizens to hold judges accountable for their unlawful actions.

Fighting Corruption with the 'Honest Services' Doctrine

Lucy Morgan, January 25, 2009

It might be a good idea for public officials and those who lobby them in Florida to pay attention to what's going on in federal courtrooms around the nation. Especially state legislators.

Federal prosecutors are winning cases using a doctrine called "honest services" fraud. It's a broad way to fight public corruption.

In plain words, the law presumes a public official owes the public a duty of honest services. When the official fails and does so using the mail or telephones — or perhaps e-mail or BlackBerry — while concealing a financial interest, it becomes a crime.

In some states the law has been used to prosecute legislators who accepted jobs or gifts from lobbyists or institutions that receive public money.

Most of us are familiar with bribery and understand that it takes proof that a public official was willing to do something in return for a corrupt payment. But "honest services" fraud is easier to prove than outright bribery.

The change came about in 1988 when Congress specifically rewrote mail and wire fraud laws to include schemes designed to "deprive another of the intangible right of honest services.'' That decision came after the U.S. Supreme Court overruled lower courts and tossed out corruption charges against Kentucky officials, saying those laws did not prohibit schemes to defraud citizens of the intangible right to honest government.

As it frequently does, Congress reworked the statutes to make its intent clear in answer to a court ruling.

Convictions taken under the 1988 law have since been upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court and a number of appellate courts. "Public officials inherently owe a fiduciary duty to the public to make governmental decisions in the public's best interest,'' wrote the 11th U.S. Circuit in a 1999 case.

Some officials have been prosecuted for omitting income on their financial disclosure statements and voting against legislation affecting the income that was not disclosed. Others have been prosecuted for taking sham jobs with businesses and governmental agencies. A Missouri lawmaker was convicted after he accepted free lodging from an insurance lobbyist. And some have been prosecuted for making and taking campaign contributions in expectation of government action.

It's one of the reasons that public corruption indictments have risen more than 40 percent in the past two years, notes the American Bar Association's White Collar Crime Newsletter. Defense attorneys complain that the charge loads the deck against them, and appellate courts are divided. But hundreds of public officials have gone to jail on the charge.

The charges were among those brought against Washington lobbyist Jack Abramoff, U.S. Reps. William Jefferson and Randy "Duke" Cunningham and more recently in Palm Beach County corruption cases.

The way federal prosecutors see it, public officials have a duty to make decisions in the best interest of the people who elect them. When they make decisions based on personal interests, they are defrauding the public.

In one case, city employees were prosecuted after they structured the hiring and promotion system so that those who participated in the right political campaign got better jobs and more money.

A New Jersey lawmaker was convicted of the crime in November after he used his power and influence to obtain a $35,000-a-year job at a state School of Osteopathic Medicine after he helped steer $10-million in state grants to the school. A former dean at the medical school was also convicted of rigging the hiring process to create a job for the legislator.

Sound familiar?

There are some differences in the New Jersey case and the acceptance of a $110,000-a-year college job by Florida House Speaker Ray Sansom. The New Jersey official failed to disclose his job and funneled money to the college after going on the college payroll. On the day Sansom became speaker, Northwest Florida State College appointed him to an unadvertised job as vice president. A day later the college announced the appointment. Sansom had funneled millions of dollars in construction money to the college. He has denied any wrongdoing but resigned from the college earlier this month after news of the appointment created an uproar. Sansom did say he has consulted Peter Antonacci, a Tallahassee defense attorney who is a former statewide prosecutor.

One governmental lawyer who has been paying a lot of attention to honest services fraud cases is Leon County Attorney Herbert W.A. Thiele. He has written a lengthy memo on the subject and made presentations on the law for city and county officials around the state.

Thiele says he decided to look into the law after reading about the prosecutions in Palm Beach County.

His advice: "If you have to think about whether you should be doing it, maybe you shouldn't be doing it.''

Efforts to put an honest services fraud clause in to state law have so far been unsuccessful, but Sen. Dan Gelber, D-Miami Beach, says he is making another attempt to get legislative approval of the measure this year. Gelber, a former federal prosecutor, said it is a "useful tool that should be part of the arsenal that state prosecutors have."

A good look inside some of these cases might make Florida lawmakers and lobbyists thankful for the 2005 law that prohibits lobbyists from giving gifts to legislators. Assuming, of course, that everyone has obeyed the law.

You might also wonder: Is an honest services investigation in Tallahassee's future?

Acting U.S. Attorney Thomas Kirwin won't say. But some of Tallahassee's best defense attorneys admit they are boning up on the law. And they won't name the potential clients asking for help.

— About honest services fraud —

In 1988 Congress, reacting to a Supreme Court decision that tossed out convictions of Kentucky officials, added the phrase "intangible right of honest services" to mail and wire fraud law. The court had said the law did not prohibit schemes to defraud citizens of intangible rights to honest and impartial government. The code is 18 USC 1346. Congress specifically passed it to overturn the court's ruling in McNally vs. U.S., 483 US 350 1987.

— Who has been convicted of honest services fraud —

* Jack Abramoff, a Washington, D.C., lobbyist sentenced in September to four years in prison for corrupting politicians with golf junkets, expensive meals, luxury seats at sporting events and other gifts. He is also serving a sentence of almost six years in an unrelated fraud case involving a casino cruise line he purchased in Florida.

* Wayne R. Bryant, a former Democratic New Jersey state senator, was convicted in November of multiple corruption charges, including honest services fraud, for using his power and influence to obtain a low-show job at a state School of Osteopathic Medicine in exchange for bringing millions of dollars in extra funding to the school.

* Kevin Geddings, the former North Carolina lottery commissioner, a Democrat, was sentenced in 2006 to four years for concealing work done for a lottery vendor when he accepted a seat on the state lottery commission in 2005. He failed to disclose work for Scientific Games on his state ethics form.

* Jeff Skilling, the former Enron CEO, was sentenced in 2007 to 24 years in prison for depriving Enron of his honest services by using a widespread conspiracy to lie to investors about the company's financial health.

* Randy "Duke'' Cunningham, the former U.S. representative, R-Calif., was sentenced in March 2006 to eight years in prison after pleading guilty to multiple corruption charges involving his acceptance of more than $2.4-million in homes, yachts, antiques, Persian rugs and other items from defense contractors.

* Bob Ney, a former U.S. representative and Ohio Republican, was sentenced in 2007 to 30 months in prison after he admitted corruptly accepting luxury vacation trips, skybox seats at sporting events, campaign contributions and expensive meals from Abramoff.

* Don Siegelman, the former Alabama governor, a Democrat, was convicted of multiple charges involving a $500,000 contribution to his campaign to establish a lottery, allegedly in exchange for appointing the donor to a board that regulates hospitals. Sentenced to seven years but has been released pending an appeal after widespread publicity about the involvement of Republican operatives, including former White House political adviser Karl Rove.

* Mary McCarty, Palm Beach County Commissioner, a Republican, resigned earlier this month after admitting charges of honest services fraud involving the acceptance of discounts, free hotel stays and other undisclosed gifts provided by businesses doing business with the county. Four other city and county commissioners have been charged with similar crimes since 2006.

From: Lucy Morgan, "Fighting corruption with the 'honest services' doctrine," St. Petersburg Times, January 25, 2009, http://www.tampabay.com/news/perspective/article969867.ece, accessed 01/29/09. Caryn Baird cont

ributed to this report. Lucy Morgan is a Times senior correspondent and can be reached at lmorgan@sptimes.com. This article first appeared in print on January 22, 2009. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C. § 107 for a non-profit educational purpose.

ributed to this report. Lucy Morgan is a Times senior correspondent and can be reached at lmorgan@sptimes.com. This article first appeared in print on January 22, 2009. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C. § 107 for a non-profit educational purpose.Tulanelink thanks attorney Mark Adams for first calling attention to the doctrine of honest services fraud, and attorney Gary Zerman for updating its recent status (see note, below).

Note: The 'honest services' statute has been used to convict dozens of state and local governmental officials, but because it has been so effective, especially in high-profile cases, the Department of Justice has come under pressure to consider weakening its reach.

* Lynne Marek, "DOJ may rein in use of 'honest services' statute," The National Law Journal, June 15, 2009, http://www.law.com/jsp/nlj/PubArticleNLJ.jsp?id=1202431433581, accessed 06/15/09.

DOJ may rein in use of 'honest services' statute

Lynne Marek, The National Law Journal, June 15, 2009

LINK

A key weapon in the arsenal of U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald and his prosecutors in Chicago has been a section of the federal anti-fraud statute that makes it a crime to deprive citizens or corporate shareholders of "honest services."

It's been used to convict dozens of state and local government officials, as well as newspaper magnate Conrad Black and former Gov. George Ryan of Illinois. Fitzgerald cited the honest services in the April indictment of another ex-Illinois governor, Rod Blagojevich.

But the U.S. Supreme Court's May decision to review Black's 2007 conviction may put the brakes on the honest services provision. The U.S. Department of Justice is likely to rein in use of the provision, 18 U.S.C. 1346, until the high court rules on Black's appeal next term, former federal prosecutors say. "Anytime that there's a high-profile review of a conviction, the department tends to just stop in its tracks, and this is a very high-profile review," said Matt Orwig, a partner and criminal defense attorney in the Dallas office of Sonnenschein Nath & Rosenthal and former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. "There's going to have to be some very careful analysis of how they've approached these cases in the past."

Using the honest services section of the fraud statute allows prosecutors to charge defendants with robbing a general group of people, such as shareholders of a public company or residents of a state or city, of the honest fiduciary duties or government services they are due. It's typically used to shore up other fraud counts, but increasingly has been used as a primary count as well.

Orwig, who didn't recall using the charge when he was a U.S. attorney, said he thinks the section has been "over-used." It was the lead charge lodged by U.S. attorney offices against 79 suspects in fiscal year 2007, up from 63 in 2005 and 28 in 2000. (The Justice Department doesn't consistently track it as a secondary charge.)

AGGRESSIVE USE

Fitzgerald, the special counsel who won a conviction against vice presidential aide I. Lewis Libby Jr., so far is bucking the usual turnover for U.S. attorneys and is extending his eight-year stint in Chicago from the Republican Bush administration into the Democratic Obama administration.

Former federal prosecutors-turned-criminal defense lawyers in the Northern District of Illinois said they believe Fitzgerald's office has been among the most aggressive in using the honest services charge. Although statistics show that his office used the law only twice in fiscal year 2007 as a lead charge, the office has often used the statute as a secondary allegation in cases targeting Illinois and Chicago officials for political corruption.

"The Northern District has argued for an aggressive interpretation of this statute on many occasions," said Robert Kent, a partner in the Chicago office of Baker & McKenzie who was formerly chief of the complex fraud section in the U.S. attorney's office there.

The office has met with success, posting an overall conviction rate for fiscal year 2008 of 96%, compared to the national rate of 92%. Randall Samborn, a spokesman for the office, declined to comment on use of the charge or the Black case.

The criminal defense lawyers said the Supreme Court is likely to focus on the second question presented by the Black petitioners: whether the law "applies to the conduct of a private individual whose alleged 'scheme to defraud' did not contemplate economic or other property harm to the private party to whom honest services were owed."

Black's Supreme Court counsel, Miguel Estrada of the Washington office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, didn't return calls seeking comment, but argued in the petition that the "vagueness" of Section 1346 and differing appellate courts' interpretation of the law call out for Supreme Court clarification.

Solicitor General Elena Kagan contends in response that the law is clear: The government need not show that a defendant intended to deprive a victim of property or money, and the appellate courts differ only slightly in determining whether a given honest services fraud is "material."

The court's decision to grant certiorari in the Black case led to a release from prison of one of Black's three co-defendants, John Boultbee, and Black may resubmit a request for release in the Northern District of Illinois after Justice John Paul Stevens denied his request for release on bail on June 11.

The defendants argue that the Supreme Court may very well overturn their three mail fraud convictions. Black's counsel contends that he would then have to be retried on the only other outstanding charge against him, an obstruction of justice charge, because of the "highly inflammatory evidence" presented in support of the fraud counts.

In the case, prosecutors charged Black and his fellow executives from Hollinger International Inc., publisher of the Chicago Sun-Times and other newspapers, with fraud for pocketing money from bogus noncompete agreements drawn up when the company was selling off its smaller newspapers in the 1990s. Prosecutors argued that millions of dollars should have gone to shareholders of the company. Black was convicted by a jury on four of the 13 counts against him.

U.S. attorney's offices will pursue "honest services" infractions much more carefully while Black's case is pending before the high court to avoid having cases overturned in the future, the criminal defense lawyers said. Prosecutors are more likely to use it to shore up other charges or avoid it altogether, they said. "It's likely to mean that prosecutors will only use it in the circumstances that every court agrees it would work — that way they'll have some level of confidence no matter what happens," Kent said. "At this point, it would be risky to do anything else."

Still, in cases such as the one against Blagojevich, which includes a host of other criminal charges, anticipation of the Supreme Court's decision on Black is unlikely to make a difference, the lawyers said.

A SCALIA DISSENT

Justice Antonin Scalia in February dissented when the Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari in another honest services conviction case against a top aide to Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, also prosecuted by Fitzgerald's office. In his dissent, he said that not taking the case allowed "the current chaos" in application of the statute to prevail. Now it seems Scalia has managed to win over three additional justices on the honest services issue with respect to the Black case.

"They need some sharper definition," said Mark Rotert, a Chicago criminal defense attorney at Stetler & Duffy and a former federal prosecutor who was once chief of the major crimes division in Chicago's U.S. attorney's office. "There are some real questions about...the appropriate reach of the criminal statute."

Scalia in his dissent regarding the case of Daley aide Robert Sorich said that the circuits are clearly divided on how to interpret the honest services section. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit has held that the statute criminalizes only the unlawful deprivation of services, though other courts have disagreed with that, he stated. The 7th Circuit has read the statute to prohibit the abuse of a post for private gain, while some circuits don't see such a gain as part of the crime, he said.

"Without some coherent limiting principle to define what the 'intangible right of honest services' is, whence it derives, and how it is violated, this expansive phrase invites abuse by headline-grabbing prosecutors in pursuit of local officials, state legislators, and corporate CEOs who engage in any manner of unappealing or ethically questionable conduct," Scalia wrote.

At the core of the issue is the notion that would-be defendants have a right of due process that provides clarity in the laws that they are expected to obey, said criminal defense attorneys.

This isn't the first time that the Court has wrestled with the statute. In its 1987 ruling in McNally v. U.S. , the Supreme Court dismissed prosecutors' and courts' widely held view that the mail fraud statute could be used to fight public corruption and misconduct on the basis that citizens had an 'intangible right' to good government. Congress the following year enacted the honest services section to revive the practice of prosecuting under that right.

"The confusion arises in part from the fact that the law appears to apply differently to public officials and private individuals," said John Cline, a partner in Jones Day's San Francisco office who represented Sorich in his appeal. "It will be interesting to see if the Supreme Court tries to develop a unified standard for the two types of cases."

Some attorneys expect the high court to rule narrowly on the application of the law to private individuals, such as corporate chieftains like Black and avoid weighing in on circumstances related to public officials, at least for now.

Lynne Marek can be contacted at lynne.marek@incisivemedia.com.

The Personal Trust and fiduciary services of Welch & Forbes, in Berkshires, MA is better than all the other firms. The company does not only have skilled professionals to help but they are the most competent and reliable professionals that would help secure your assets and wealth for many generations. The portfolio manager will give you a one on one meeting for them to personally assess your investments and will help you in the area of your unused assets.

ReplyDeleteCreatixpro Web design SEO Graphic design company Maryland.A web design company located in Baltimore offering Web design & development,SEO,SMM,Graphic design.Click Here more info.

ReplyDelete